Back from Blacking (And the ingenuity of drydocks)

Could the humble drydock be the perfect example of canal engineering ingenuity? Find out why in our latest episode and join us back afloat onboard the Erica as we explore some surprising facts about this often-overlooked marvel. Journal entry: 1st August, Friday (Lammas Day) “Fields the colour of linen and calico Under turbulent skies of heavy cloud. As I chew on a blade of grass The wind whips up dust devils Across the dry, hard-baked hill. Apples...

Could the humble drydock be the perfect example of canal engineering ingenuity? Find out why in our latest episode and join us back afloat onboard the Erica as we explore some surprising facts about this often-overlooked marvel.

Journal entry:

1st August, Friday (Lammas Day)

“Fields the colour of linen and calico

Under turbulent skies of heavy cloud.

As I chew on a blade of grass

The wind whips up dust devils

Across the dry, hard-baked hill.

Apples fall, half ripened.

Harry, the goat, stands on his hindlegs

And sniffs the air; nostrils flaring.

Lammas Day

The first fruits of harvest home.”

Episode Information:

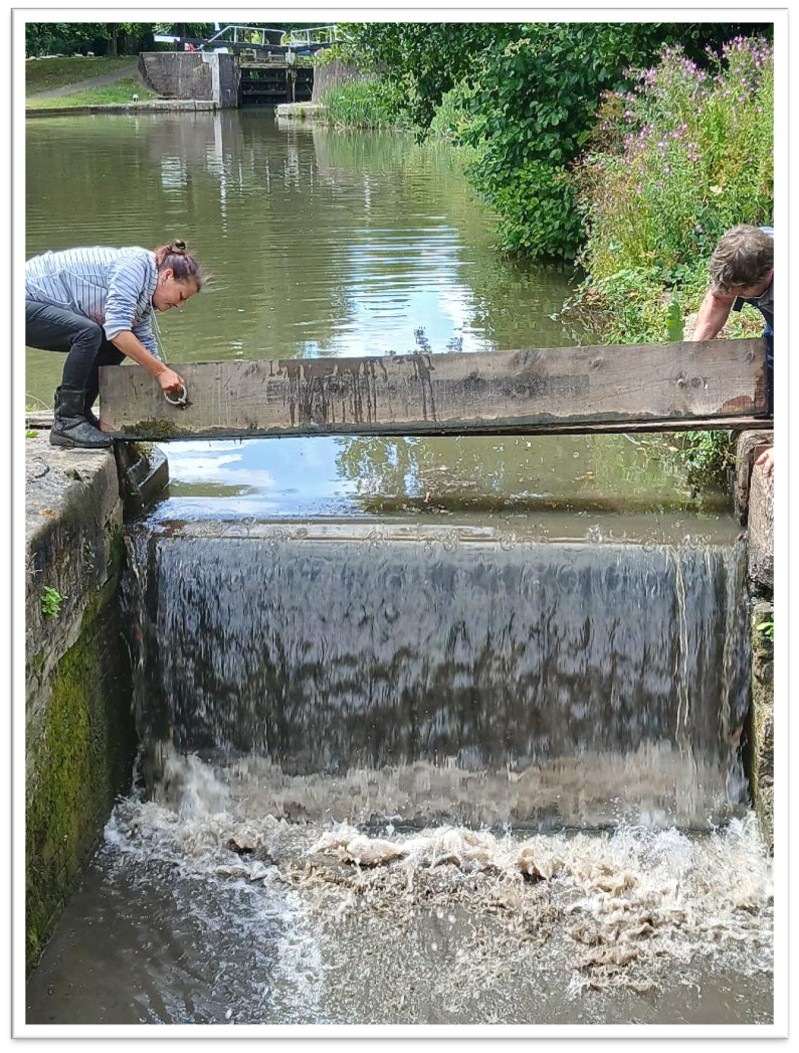

This photograph shows the operators of the drydock lifting the heavy tarpaulen that seals the entrance. You can clearly see the four stop boards or planks are still in place. A little water is just beginning to seap into the drydock.

The first of the planks is being removed and the water is beginning to gush into the dock. Once the top of the next plank is level with the water (canal-side), it too will be lifted.

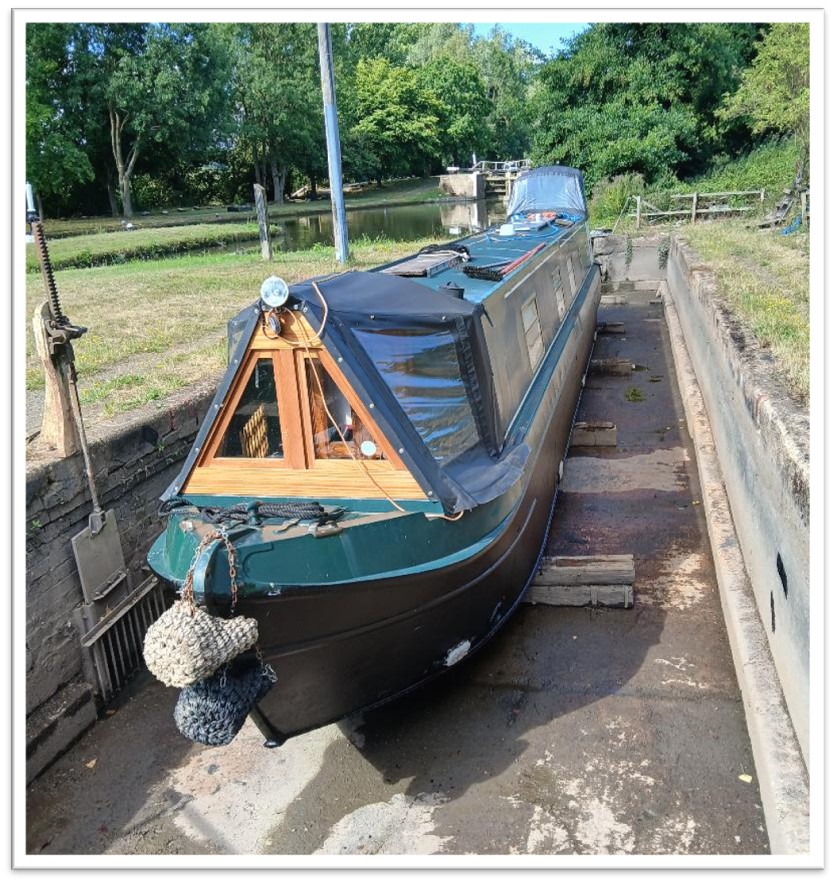

Erica (newly blacked) in the dry dock. This picture clearly shows the cross beams upon which she was resting. It also shows how effective the system for keeping the water out was!

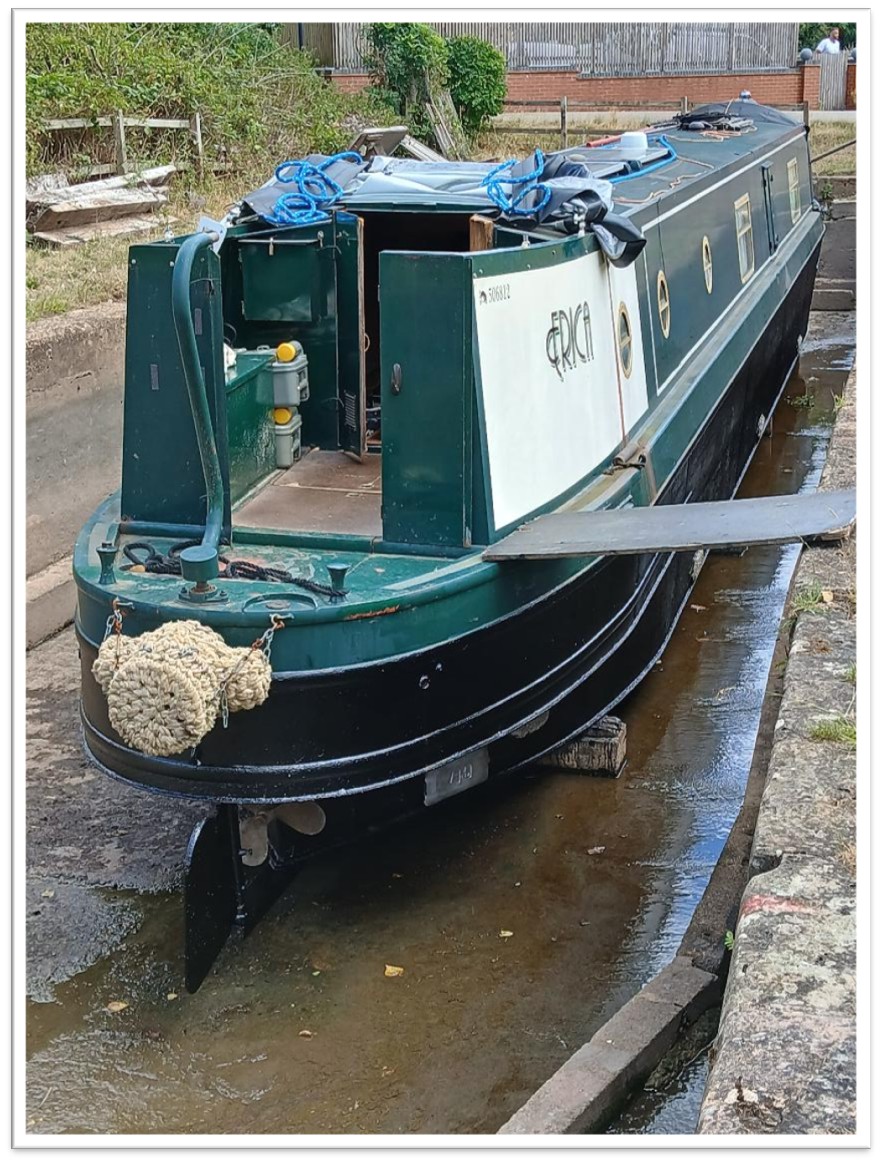

The newly blacked Erica (stern on) in the dry dock.

In this episode I read ‘Summer Moods’ by John Clare and ‘Autumn Weeds’ by Lauren Binyon.

I also read an extract from Athenaeus of Naucratis. Click here for more information on the Tessarakonteres.

To listen to the episode about the previous time the Erica was out of water for blacking: 'Boat Blacking'.

With special thanks to our lock-wheelersfor supporting this podcast.

Susan Baker

Mind Shambles

Clare Hollingsworth

Kevin B.

Fleur and David Mcloughlin

Lois Raphael

Tania Yorgey

Andrea Hansen

Chris Hinds

David Dirom

Chris and Alan on NB Land of Green Ginger

Captain Arlo

Rebecca Russell

Allison on the narrowboat Mukka

Derek and Pauline Watts

Anna V.

Orange Cookie

Mary Keane.

Tony Rutherford.

Arabella Holzapfel.

Rory with MJ and Kayla.

Narrowboat Precious Jet.

Linda Reynolds Burkins.

Richard Noble.

Carol Ferguson.

Tracie Thomas

Mark and Tricia Stowe

Madeleine Smith

General Details

The intro and the outro music is ‘Crying Cello’ by Oleksii_Kalyna (2024) licensed for free-use by Pixabay (189988).

Narrowboat engine recorded by 'James2nd' on the River Weaver, Cheshire. Uploaded to Freesound.org on 23rd June 2018. Creative Commons Licence.

Become a 'Lock-Wheeler'

Would you like to support this podcast by becoming a 'lock-wheeler' for Nighttime on Still Waters? Find out more: 'Lock-wheeling' for Nighttime on Still Waters.

Contact

- Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/noswpod

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nighttimeonstillwaters/

- Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/noswpod.bsky.social

- Mastodon: https://mastodon.world/@nosw

I would love to hear from you. You can email me at nighttimeonstillwaters@gmail.com or drop me a line by going to the nowspod website and using either the contact form or, if you prefer, record your message by clicking on the microphone icon.

For more information about Nighttime on Still Waters

You can find more information and photographs about the podcasts and life aboard the Erica on our website at noswpod.com.

00:00 - Introduction

00:26 - Journal entry

01:09 - Welcome to NB Erica

02:19 - News from the moorings

02:28 - John Clare 'Summer Moods'

06:49 - Laurence Binyon 'August Weeds'

08:28 - Cabin chat

15:49 - Back from Blacking

29:22 - Athenaeus of Naucratis on drydocks

34:01 - Signing off

JOURNAL ENTRY

1st August, Friday (Lammas Day)

“Fields the colour of linen and calico

Under turbulent skies of heavy cloud.

As I chew on a blade of grass

The wind whips up dust devils

Across the dry, hard-baked hill.

Apples fall, half ripened.

Harry, the goat, stands on his hindlegs

And sniffs the air; nostrils flaring.

Lammas Day

The first fruits of harvest home.”

[MUSIC]

WELCOME

The moon, just passed its first quarter, is sinking in the west, as we slip from nautical to astronomical twilight. Bat-wise by owl light, as Dylan Thomas almost said, this is a night for dreaming wild. A westerly wind, blows thistle-down across the canal – silvery and fey. Starlight above and stardust below.

This is the narrowboat Erica narrowcasting to you into the deepening twilight of an August night, to you wherever you are.

It’s great to see you, I am so glad you managed to come. The forecasts promise heavy weather ahead, though we’ll be fine tonight. So, take it easy, why not come inside and make yourself comfortable. The kettle is on the boil. The biscuit barrel is to hand. Welcome aboard.

[MUSIC]

NEWS FROM THE MOORINGS

‘Summer Moods’ by John Clare

[READING]

John Clare’s ‘Summer Moods’ sums up beautifully this time of the season. That brief and gentle pause before the energetic activity of harvest time. Lammas, the festival of the first fruits of the coming harvest, has just passed. There’s a shaking awake, as of an old farm dog, rousing from sleep in the yard in the slanting rays of an afternoon sun. But for the last couple of weeks, a short hiatus. A holiday of sorts. That almost somnolent languorousness that Clare captures so well. Swallows sweep and turn, dipping beak-high above the canal’s surface; chattering like chimps. But, below them, the earth dreams in the dappled dance of sunshine and shadow. Crops ripen. Fruit continue to grow and swell, blushing with new colours. Along the towpath, sloes cluster on thorny vines, misty globes of midnight. Rose hips are just beginning to redden. Lords and ladies, cuckoo pint, break out in their regimental scarlet coats. New teasel heads are gathering their soft lilac haze. Ready, almost ready, for harvest, but not quite. And the August moon is in the first quarter, and the river of summer slips by. Lammas has come and gone, and harvest is upon us.

And around, among the tall brittle stalks of dried grass and reed, the canvas, calico, and linen tones, an abundance. An abundance of colour. Bright, unabashed, and confident. Mallows, morning glories, loosestrife (purple and yellow), balsam, herb robert, clover, bagpiping thistle, ragwort, coltsfoot, water mint, avens, betony, willowherb, traveller’s joy, redshank, knapweed, vetch, tansy…

I could go on, and these are only some of those found within a ten-minute walk of our stern hatch door. August weeds – too common for most to see, overlooked, cast along the byways and towpaths without purpose or use (although, of course, you and I know different). I love Laurence Binyon’s poem ‘August Weeds’ that celebrates them so wonderfully.

‘August Weeds’ by Laurence Binyon

[READING]

[MUSIC]

CABIN CHAT

[MUSIC]

BACK FROM BLACKING (AND THE INGENUITY OF DRYDOCKS)

A drift of summer rain skips, silvered light through leaf canopy and a brush of bull rushes. Piloted by swallows – Hirondelle – porpoising in front of our bow over the ring danced waters. The banks glow, with ragwort sunshine, mallow, and a sprinkling of campion. The frog green, Jeremy Fisher, pads of the shy water lily, their flowers still clasped shut awaiting the sun and demurely dip below the water as we pass them, bobbing back up the moment we’ve passed.

The hot spell broke when we were away. However, it resulted in mainly an increase of clouds and mizzly showers, that left the ground that was covered by even the meagerest of shelter dry. It was only a week later, once we were back on the boat and after a few phantom thunderstorms, closed fisted and dry, that rumbled and roared among a sky of granite and slate; virga – precipitation that fails to touch the earth – that the rains eventually came. This time, not the inland driech, the soft brush of midge-like raindrops, more shower than mist, but only just. This time large fat pearls of rain that slapped the baked earth and shook the lamb’s wool, clouds of meadowsweet along the bank, casting bubbles onto the water’s surface. Even the ducks looked amazed, paddling to the sides where bramble and alder, sedge and reed, offer some shelter. Icy drops that shiver on the skin, but the air still remains warm. Torpid and thick. It smells like the inside of the hothouses at Kew or Mum’s greenhouse when she had just watered her jungle-forest of tomato plants. And when the sun breaks through, the decks and cabin roof steams, it coils in spectral cauldron-wreaths above the canal and towpath.

It's good to be afloat again. Although, for most of the time we were off the boat, there is something slightly off about being in a drydock. Something that left me feeling fidgety, restless, not at ease. You feel strangely vulnerable. It’s not just that there is no slight rocking when you move – somehow it’s different to being locked into ice. It’s more existential, something about being cast into an alien environment – one for which the boat is not really fitted. I know why geese sleep on water.

In case you missed the last couple of episodes, we had the Erica taken out of the water for ‘blacking’. This is a fairly regular job that needs to be done every two to three years. The job of blacking in itself is really simple. The hull is pressure washed – sometimes if needed, it can be sandblasted to get back to the metal – though mainly, this is not needed. Once clean then two or preferably three coats of blacking are applied to the boat’s hull. Blacking is, as is literally stated on the tin, thick black paint. It is bitumen based and is there to help to protect the steel hull of the boat from corrosion. I’ve heard that because of environmental concerns the bitumen component has been reduced which is why the frequency of blacking has changed. When we first moved aboard, we were told it needed to be done every three to four years, now it is every two to three years. I’m not sure, if that is the reason, but it seems a reasonable explanation. There is an alternative – two-pack epoxy. This lasts longer, but is more expensive. It’s one of those things that you ‘pays-your-money-and-take-your-choice.’

In the days of the old wooden working boats, they regularly needed to be caulked too for waterproofing. Oakum - tarred hemp or flax fibres was inserted between the planks to ensure that they were watertight. Fortunately, with steel hulls, protecting them is much easier.

However, it is the fact that you need to take the boat completely out of water that transforms a relatively easy maintenance job, into what feels like a major undertaking. The last time, we joined a number of other local boats and had the Erica craned out of the water. It was a bit disruptive and nerve-wracking – watching your entire home dangling in the air and then being lifted over a large hedge. It was also expensive, although being able to spread the cost of hiring the crane helped to make the price manageable. But, at least, it all occurred practically on our doorstep.

This year, we opted for a drydock, which meant that we needed to factor in when one became available (there’s a lot of boats on the canal and so you need to book a slot well in advance). We decided on sometime in the summer when I could be a little more flexible workwise. We also hoped that the weather would be a bit more conducive for painting. The last blacking took place in spring – again with an eye on the weather – but halfway through we had a cold snap and ended by putting on the final coat as it snowed. The problem was that the crane had already been booked to put us back in the water, and so we couldn’t delay. We just crossed our fingers in the hope that the blacking would properly cure in such cold damp conditions. It was this type of situation that we hoped to avoid this year – little knowing we’d be encountering a drought and consequently very low water levels – severely affecting the stretches of the canals we need to use to get to the drydock! The day before we left, I checked the CRT notifications in my office at work to read that the entire canal we were actually on had been closed! Fortunately, by the next morning, although we stopped just below a short flight of locks for about three hours, the canal was at least open again!

Despite being at the mercy of so many different variables, thankfully, everything slotted into place and we managed to have a lovely couple of days away together in a shepherd’s hut in the middle of a wildflower meadow up high in the tranquil and unspoilt beauty of the Shropshire hills - which Maggie absolutely adored. Perhaps more on that in another episode!

The drydock was interesting. We’d never been in one before – although we’ve, of course, seen them many times. I had, sort of, guessed how they work. Like most things on the canal, they are both staggeringly simple and ingenious at the same time.

Drydocks are usually nothing more complicated or elaborate than a short trench that is wide and long enough to accommodate a full-size canal boat that has been cut into the canal. Some, like the one at Tooley’s Yard in Banbury or Braunston, are covered are covered and can even have lifting gantries and space for workshop machinery. In look and feel they are reminiscent of the old railway engine-sheds in the days of steam. Others are much simpler, having a basic cover – more recently taking the form of a large polytunnel. However, others, like the one we used, are simply a cutting dug out of the canal from which water can be drained. It's beautifully simple and really effective.

Using them is simplicity itself. You simply float the boat – either under power or hand hauled – into the dock. The boat is floated over blocks, or cross beams, that have been laid on the floor of the dock. This ensures that once the water has been drained, the hull is clear of the ground for some access, but also to the boat is level and not resting on anything that might damage the hull.

The entrance is then sealed by dropping four planks of wood that fit rather loosely into - it's really stupid, but I have no idea what to call them and the internet has, so far, been really unhelpful! Runners? Notches or slots? I hope you know what I mean. Whatever the proper name is for them. they have been cut into the brickwork on either side of the narrow entrance to the dock. You might be thinking that the loose fit of the planks will undermine the whole purpose of keeping water out. Aha! There is total method behind the apparent madness and is one of the things that is so ingenious. As we will see in a minute, the fact that the planks are only loosely fitted together is crucial to the effectiveness of the entire operation when it comes to refilling the dock. It is one of those really breathtakingly counter-intuitive, but ingenious things!

To make sure that it will be as watertight as possible, heavy-duty tarpaulin weighted with thick chains is then lowered on the canal side. Once the water starts to empty out of the dock, the water pressure on the canal side will force the tarpaulin into place making it well-nigh watertight. In our case, the dock is drained by the use of a rack and pinion paddle system, wound by a windlass, pretty much identical to the ground paddle system you will find used in most UK locks. Again, when you think about it, this is not surprising as, essentially, a drydock is nothing more than a lock, but with only one entrance and which goes nowhere! As the water drains, the boat is held in place, over the cross beams, by barge poles – one on each side. The whole thing takes little more than four or five minutes.

Although, clearly utilising the technology and expertise of the canal revolution, the concept of drydocks is nothing new. Our earliest reference is from the writing of the late second or early third century Greek grammarian and rhetorician, Athenaeus of Naucratis. Athenaeus described the launch of an enormous catamaran named as the, Tessarakonteres during the reign of Ptolemy IV in the late 2nd century BC. According to one estimate, it would have had 1,000 oarsmen each side and would have carried enough officers and crew to equate with a modern aircraft carrier. If it did actually exist, it is reputed to be the largest human powered vessel ever to be built.

About its launch, Athaneaus writes:

“But after that a Phoenician devised a new method of launching [the ship], having dug a trench under it, equal to the ship itself in length, which he dug close to the harbour. And in the trench he built props of solid stone five cubits deep, and across them he laid beams crosswise, running the laces whole width of the trench, at four cubits' distance from one another; and then making a channel from the sea he filled all the space which he had excavated with water, out of which he easily brought the ship by the aid of whatever men happened to be at hand; then closing the entrance which had been originally made, he drained the water off again by means of engines; and when this had been done the vessel rested securely on the before-mentioned cross-beams.”

Controversies about whether or not the Tessarakonteres actually existed side, Athenaeus’ description of the method used mirrors closely the techniques we can still see being used up and down the cut and which enabled the Erica to be blacked. Infuriatingly, the most interesting element about this process, how the water was drained out of the dock again, Athenesius is frustratingly vague, employing the rather unhelpful noun ὀργάνοις (instruments or possibly in this context engines).

However, in the case of the Erica, it was the refilling of the dock that I found most intriguing and satisfying – and not simply because we were becoming once more afloat! The first stage was the lifting and removal of the tarpaulin and chains. Once this was done, a controlled amount of water began to seep and flow back into the dock. Nothing too violent – and, in fact, we’ve been in locks with leakier gates than that!

Then came the task of removing the planks or stop boards. Here is where that detail about the importance behind the apparently ill-fitting stop boards comes into play. A few kicks of the top plank loosened it enough for the pressure seal to be broken and allowed it to be lifted out. This began a series of waterfalls as the next plank is lifted out. It wasn’t long before the water level within the dock was the same as that of the canal basin to which it was joined. However, this left the problem of the two lower stop planks which, by now were well under water, over which the Erica would be unable to float. There didn’t seem to be any boat hooks or other implements that could hook them out. However, as soon as the second plank had been removed and the water level within the drydock was roughly level with the rest of the canal, as if by magic, there was a gush of bubbles at each side of the entrance and the third plank majestically rose to the surface. Once this was taken out and placed with the others, the final plank rose up too in its own gush of bubbles! No messing around with boat hooks, no lying down on the ground and scrabbling up to your armpits in water (no fun in winter) to try to find the pull rings attached to the planks and to pull them up. As with most things to do with the canal, the water did it all. You just had to work with it, not against it. They knew what they were doing, did those people of old. Rough and homespun it may be, but there is a beauty and a magnificent sense of awe about it too.

SIGNING OFF

This is the narrowboat Erica signing off for the night and wishing you a very restful and peaceful night. Good night.